Pierre Paulin

1927 - 2009

1927-1947 A war-time childhood

Pierre Paulin was born in 1927 to a French father and a Swiss-German mother. He grew up in a family where order and discipline were key values. The Paulin family reluctantly moved to Laon, Picardy, following the worldwide stock market crash in 1929. The young Pierre disliked school, and this boisterous and dreamy student ended up in a boarding school in 1938. He had to move once more, this time with his family to the Gers, due to the outbreak of war. However, his stay in the countryside led to his discovering his creative passion and talent, thanks largely to his first conversations with his uncle, Georges Paulin, a car designer for Peugeot and Bentley and an aeronautical engineer specializing in aerodynamic design. His uncle would have a huge impact on how Pierre Paulin approached form and style. From an early age, Pierre Paulin designated art as his ultimate value, whilst at the same time refusing to call himself an artist. ‘I don’t create, I devise, I design. »

1947-1950 A real artistic flair

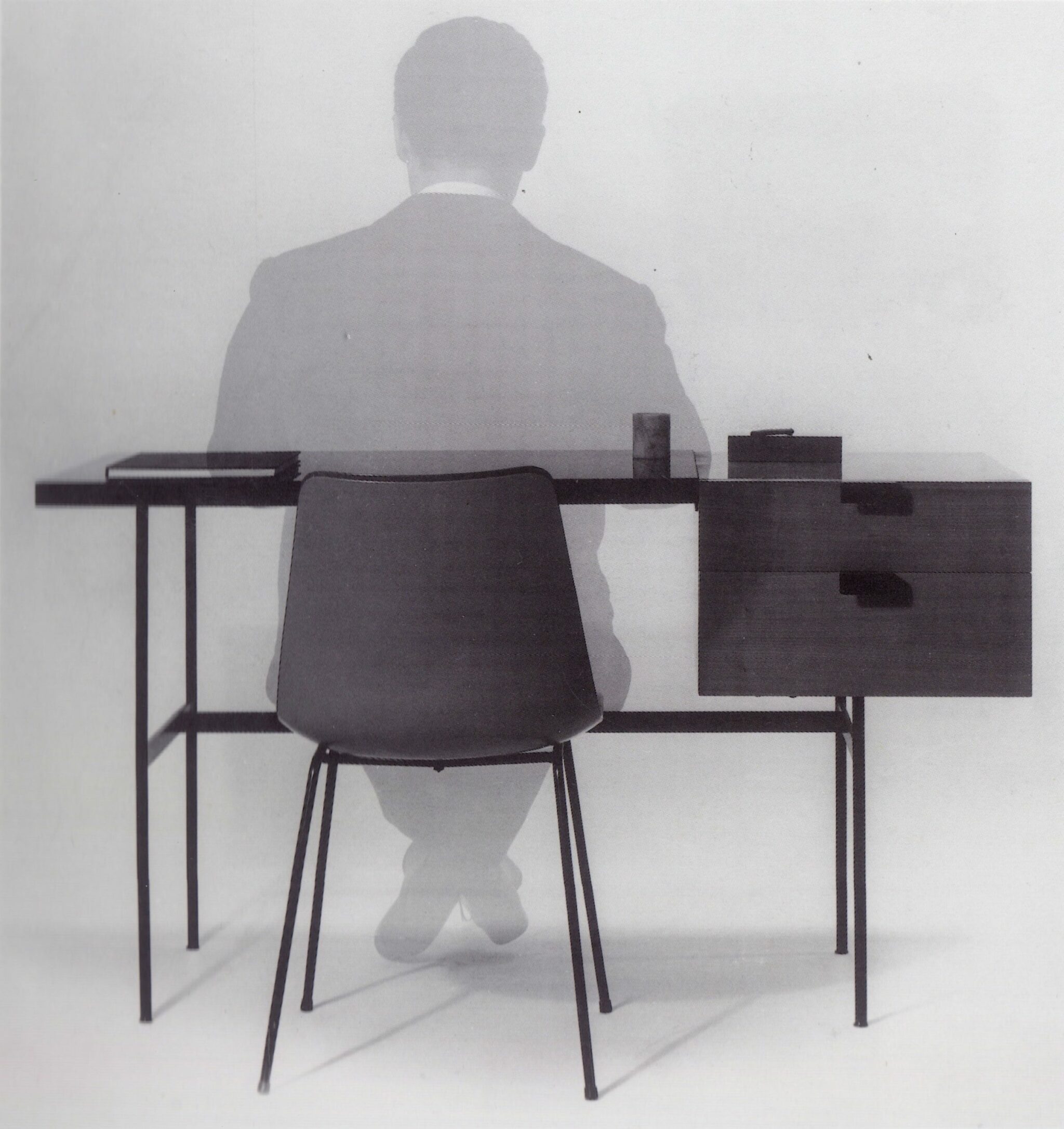

With the return of peace and the liberation of Paris at long last, Pierre Paulin enrolled in the Centre d’Art et de Techniques (soon to become the Ecole Camondo) in 1947. Here he was to meet his colleague Janine Abraham for the first time, before they both ended up working for furniture manufacturer Meubles TV. It was a time of experimentation, both in the practical and the artistic spheres. He began his training in ceramics in a workshop in Vallauris. ‘It was all happening there. I saw people like Picasso, who at the time was making ceramic artwork at Madoura, where I learnt my trade3 ». The following year he left for Beaune, following in the footsteps of his great-uncle, Fredy Balthazar Stoll, a contemporary of Rodin, who was to introduce him to stone carving. Unfortunately, an injury forced him to give up on the idea of a career in this field. Henceforth, he devoted much of his time to sculpting synthetic foam, a much more modern material than marble. At the école Camondo, his professor of design, Maxime Old instructed him in the role of interior designer and how to develop a feeling for proportions: ‘Old’s presence was a real encouragement. Later on, I realized that learning Latin and familiarizing myself with a full range of decorative styles had given me a more rounded vision and a knowledge of the past which helped me to advance towards the future4». On the 10th of July 1950, a just-graduated Pierre Paulin created, with the help of his father, his first two designs: a plywood chair and a desk.

1951 The search for inspiration

On Old’s recommendation, the young graduate spent a short period of time at ARHEC,5 6Marcel Gascoin’s design agency

He recalled: ‘Gascoin, as he’d done for so many others, acted as a kind of catalyst for me. And what a catalyst. I could even see myself working on a kind of socially- responsible form of interior design’. The young man finally found his niche: ‘mass production, my absolute dream.’. In the magazines he found in Gascoin’s library, he discovered Scandinavian design, such as that sold by Nordiska Kompaniet. During the summer of 1951, Marcel Gascoin, the mentor for a whole generation of designers, advised Paulin, his brother and several friends to journey through Germany, Denmark, Sweden and Finland. He discovered the architecture and design work of Alvar Aalto, which was to have a massive influence on his subsequent career: ‘I finally get it! Thank you Marcel. I’m going to become Swedish. At last, with my discovery of Knoll International and Herman Miller, I feel like America has put me on the right track (…) what a revelation!’. By the time he returned, he’d made his mind up – he would focus all his energy and his drive to always prioritize function over form on mass-produced furniture, despite his mastery of form, which was one of his biggest gifts. As he liked to say, Pierre Paulin ‘draws to design, not just to draw.’. He decided to exhibit his prototypes at the next annual Salon des arts ménagers (similar to the Ideal Home Exhibition) in the contemporary mass-produced furniture category: le Foyer d’aujourd’hui. His personal life also underwent massive change in 1952, when he married Lita Sensky, who gave birth to the first!of his three children, a girl called Dominique, in the same year.

1953 L’appartement idéal

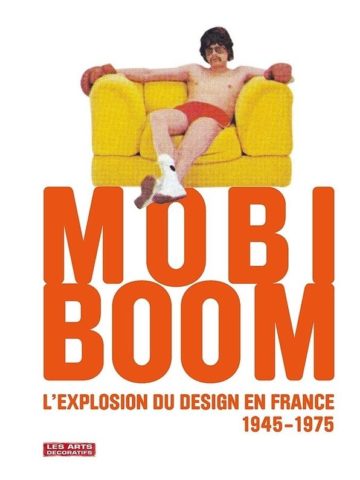

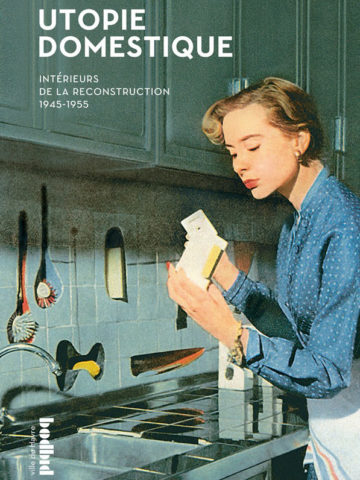

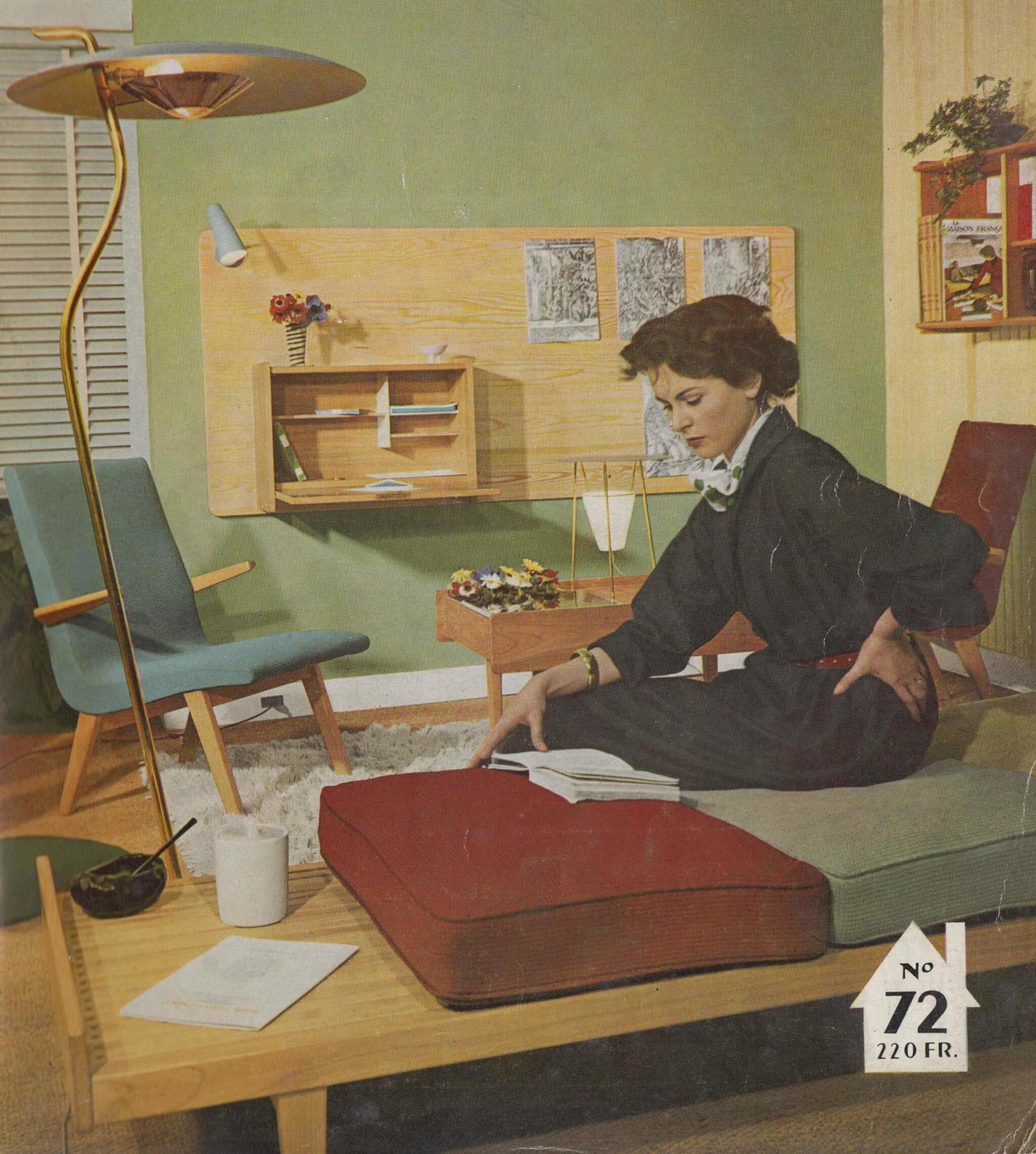

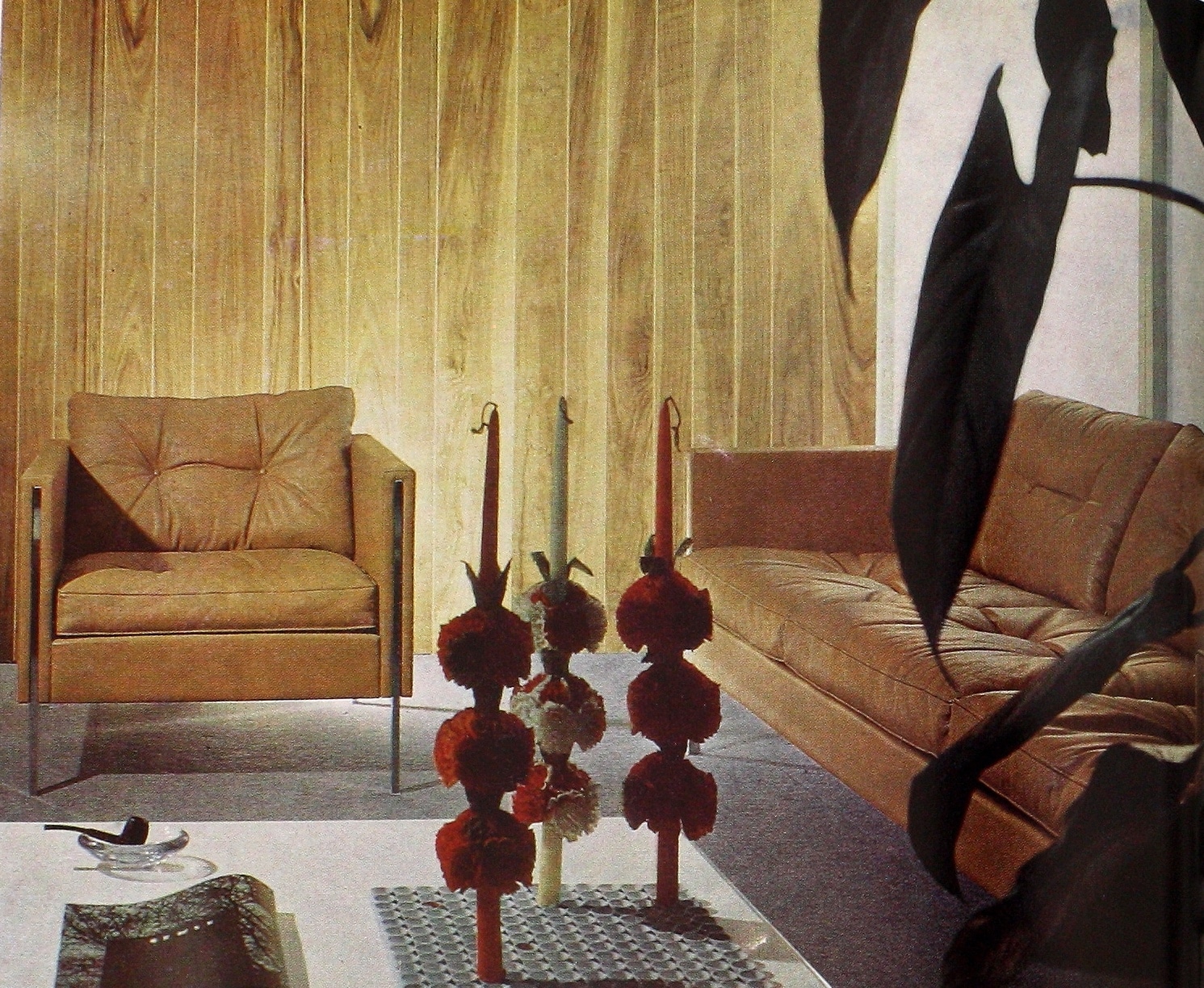

His father helped him to fund the production of his designs by a number of workshops which were beginning to venture into the field of furniture made in small production runs (Fernand Quin, Meubles TV and the Galerie MAI). He had a number of wooden furniture prototypes made, characterized by their clean-cut shapes and pared-down contours – ‘every stroke of the pencil must be perfectly accurate’.The theme of his first public exhibition, which occupied a prime spot right in the middle of the Foyer d’aujourd’hui category of the Salon des arts ménagers, was that of the new living area, to which he gave the name ‘lounge’ or ‘living-room’, with the title of the theme being ‘an ideal apartment’.

This area featured multi-purpose furniture designs, an innovative combination inspired by his recent trip to Scandinavia; a low sofa and table, a comfortable chair and a wall-mounted writing desk. He recently said: ‘When I was young, I had great admiration for what was being made in Sweden, where very simple furniture was being designed which was both elegant and aimed at people on low- incomes. I really liked that and I decided that my future would probably lie in designing wooden furniture items that would be accessible to all budgets.’

This aspiration earned him a colour front page splash in Maison française magazine13 and his first exhibition at a national trade fair was already garnering media interest. In that same year, Marie Martine Coudray wrote about him in Mobilier et décoration magazine: ‘Pierre Paulin thinks, designs and searches, obsessed by his quest for perfection. This creator of contours, furniture and other decorative objects has an attractively confident vision. We follow his artistic development with great interest’. Danielle Schirman said the following of his early period: ‘right from the start, he strove to create furniture that was carefully-designed, unfussy, well-structured, both light and sturdy and painstaking in its technical execution and finishing’. But he wanted more than just critical recognition, so, at Geneviève Pons’ request, he agreed to work for the interior design department of Galeries Lafayette. Here, in the pages of American design magazines, he discovered the top names in modern American design: Charles and Ray Eames, Harry Bertoia and Georges Nelson15. ‘I am convinced that Eames, viewed through the prism of my artistic development, is the greatest talent of his times in terms of the fundamental influence he has had upon me. Saarinen also greatly influenced my way of thinking’16. Shortly after, the first American design agency in Paris opened: ‘an absolute sensation. Knoll international has moved in right beside the church at Saint germain des prés.(…) I have the feeling of having found the direction I need to follow. Some time later, I discovered Herman Miller, which I liked even more’.

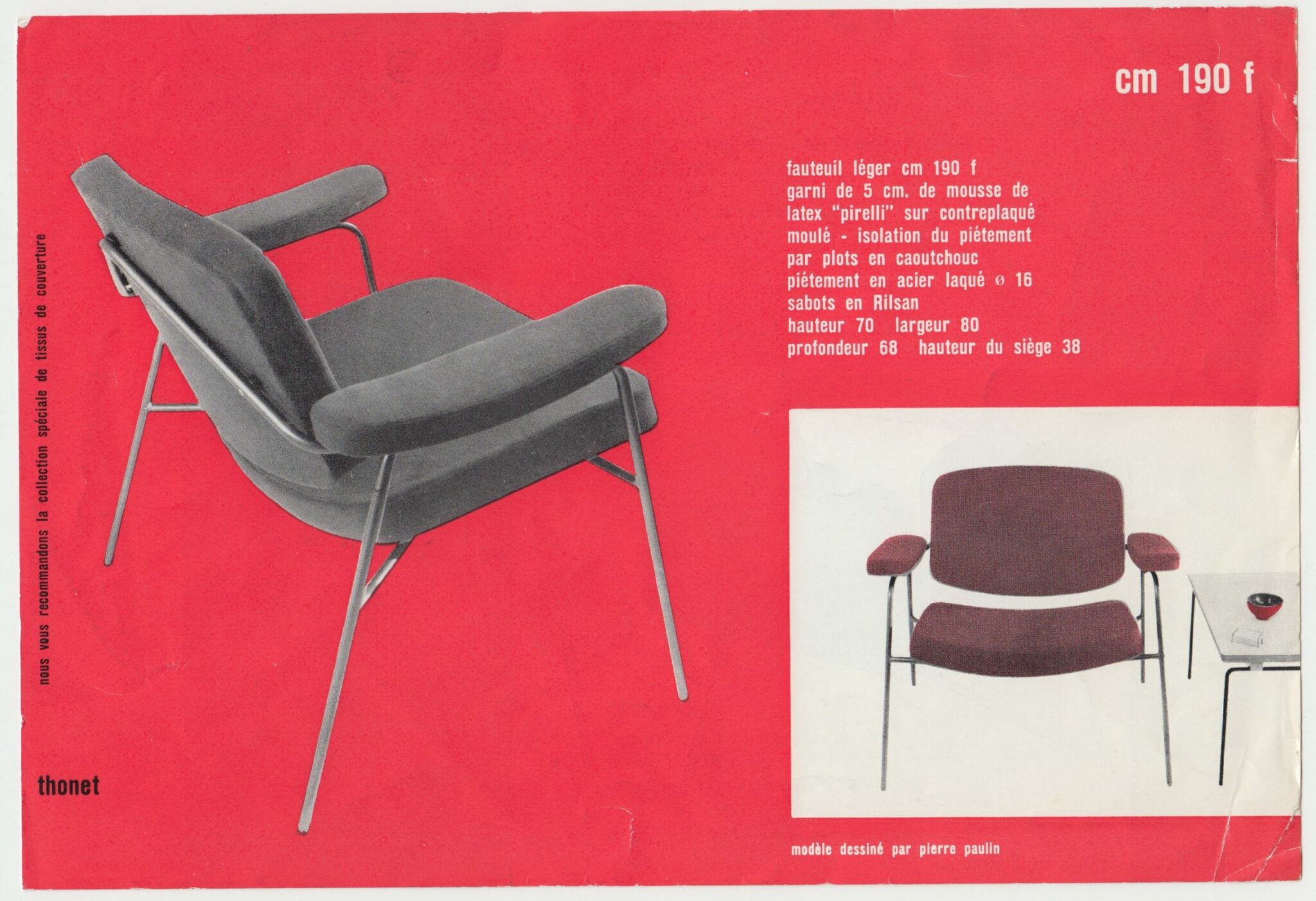

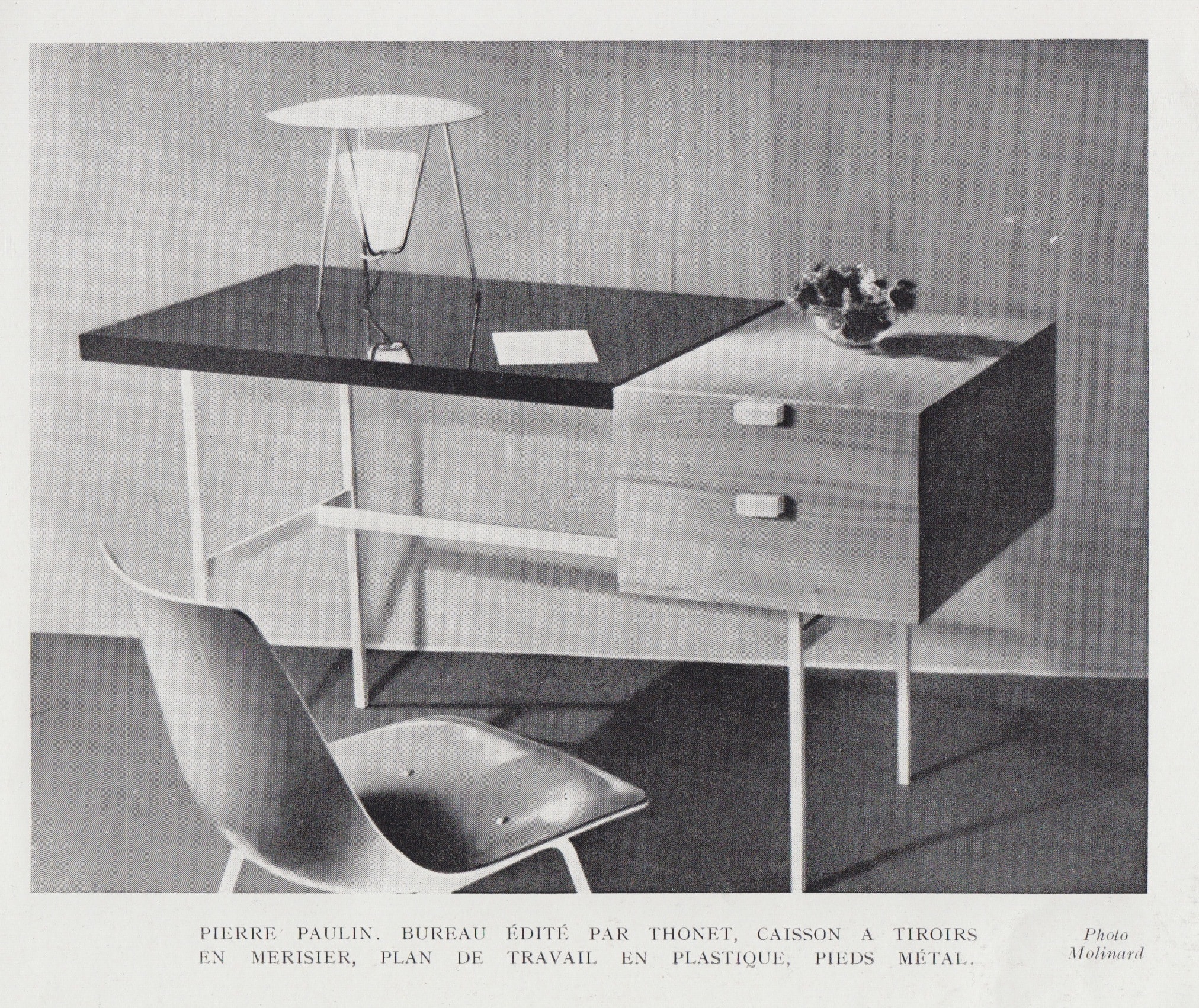

1954 Thonet – design for local government!

The following year, Pierre Paulin was taken on in the role of designer by manufacturer Thonet France, doubtless due in part to his successful showing at the 1953 Salon des arts ménagers, as well as to the involvement of André Leclerc, the company’s new CEO. Thonet played a crucial role in the development of modernism in Europe in the 1920s, making prototypes for members of the Bauhaus movement such as René Herbst, then for the Union des Artistes Modernes (Charlotte Perriand and Le Corbusier).

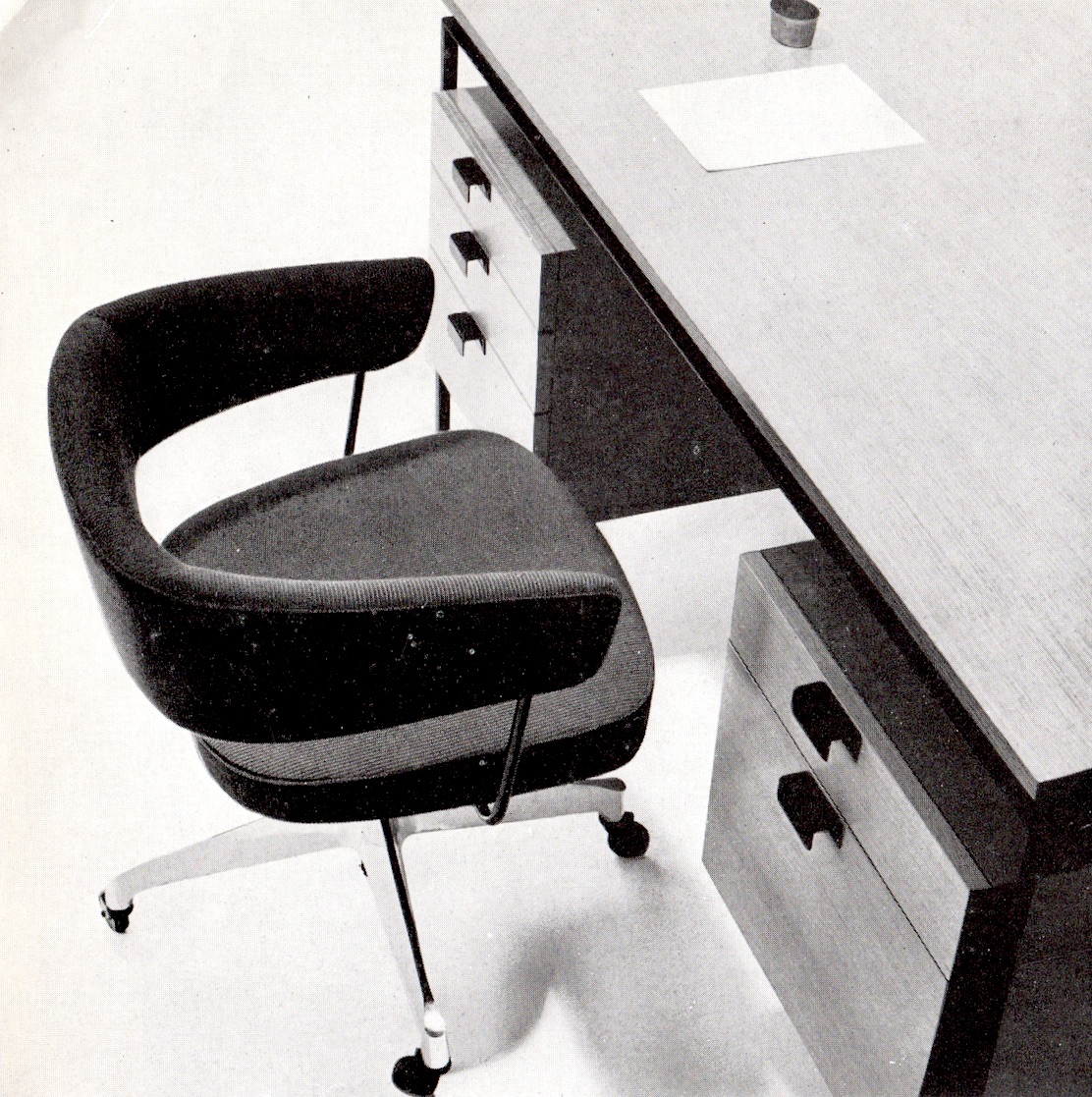

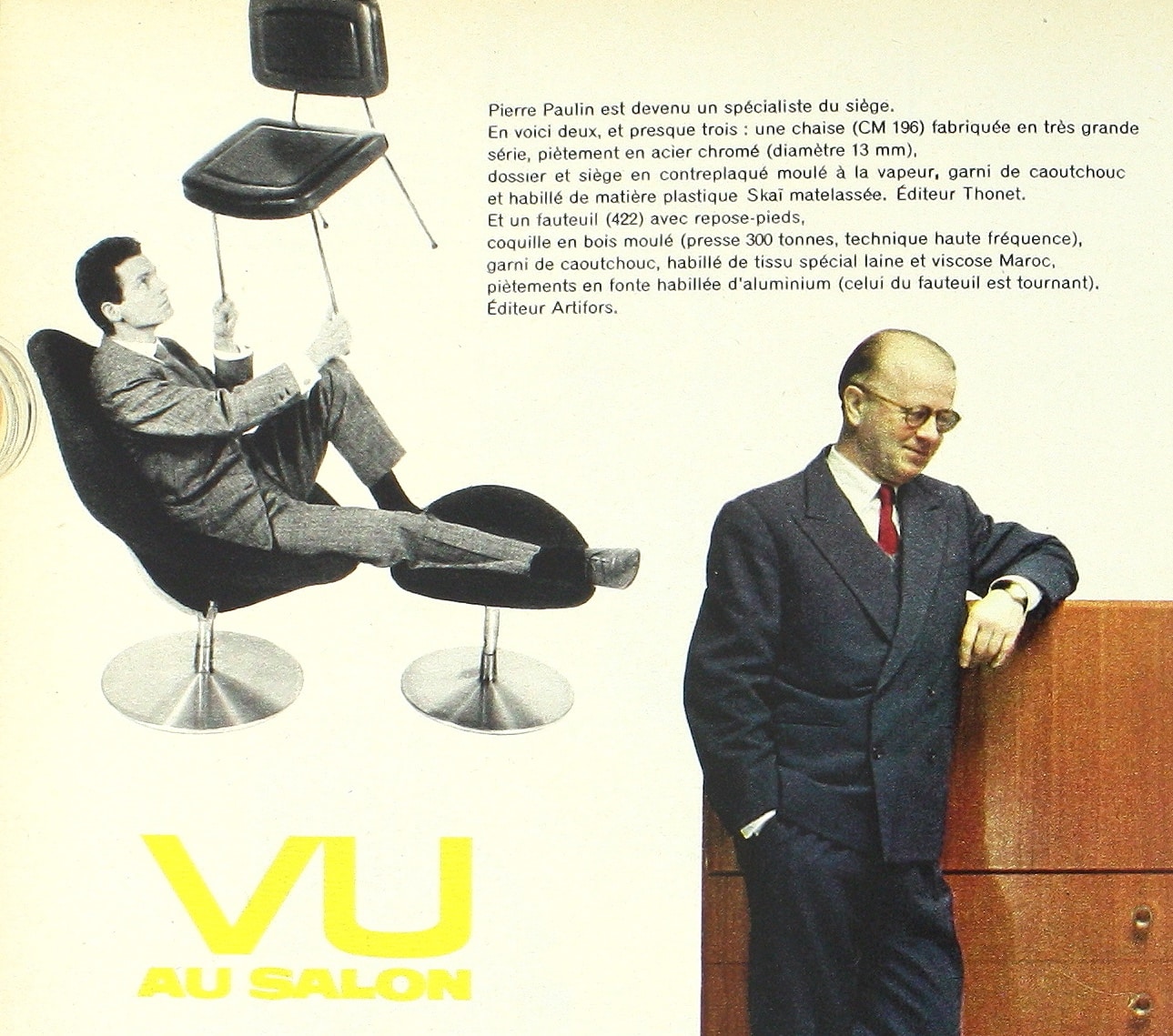

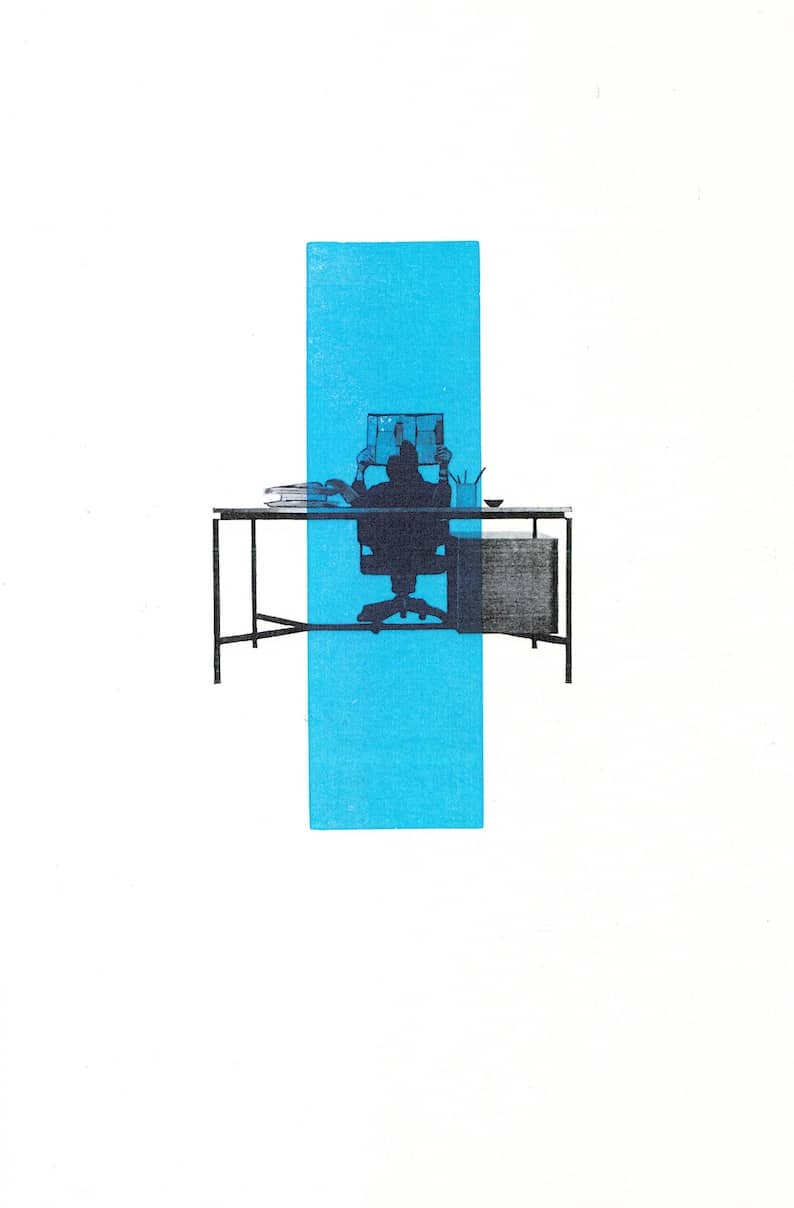

This partnership effectively began in 1954, with the presentation of his first models at the Salon des artistes décorateurs (the CM137 lounge chair in Pirelli latex foam, his famous CM141 desk and his C!M131 chair made from Bakelite-coated, moulded plywood), and lasted until 1967.

His job encompassed a marketing role as well as the creation of models and promotional material. He later took on the creative director role, developing the range of desks and seats aimed at the local government market, which had expanded after the reorganization of government at the end of the war. These models were subsequently widely produced for the ordinary consumer. The use of iron round bars and the physical separation of the different functions and parts of each design by using different materials or rubber bushings gives this range an overall look, a lightness and clarity that are second-to-none.

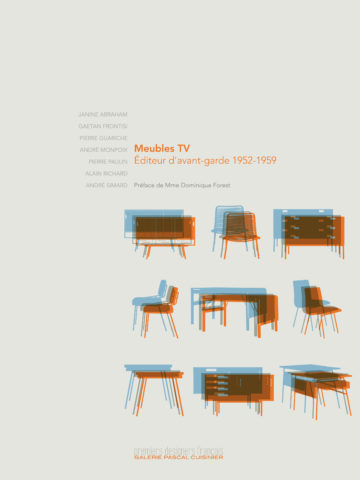

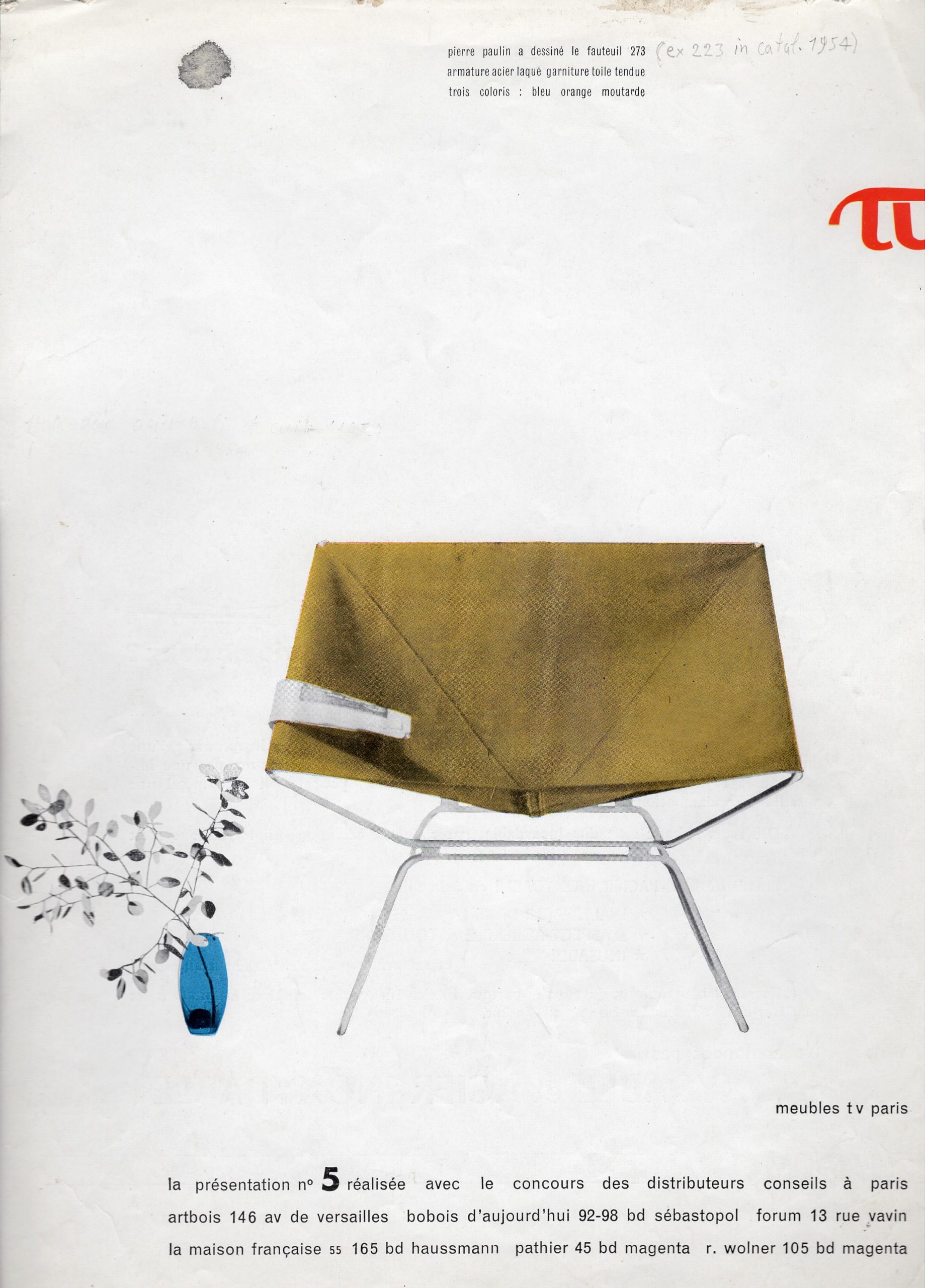

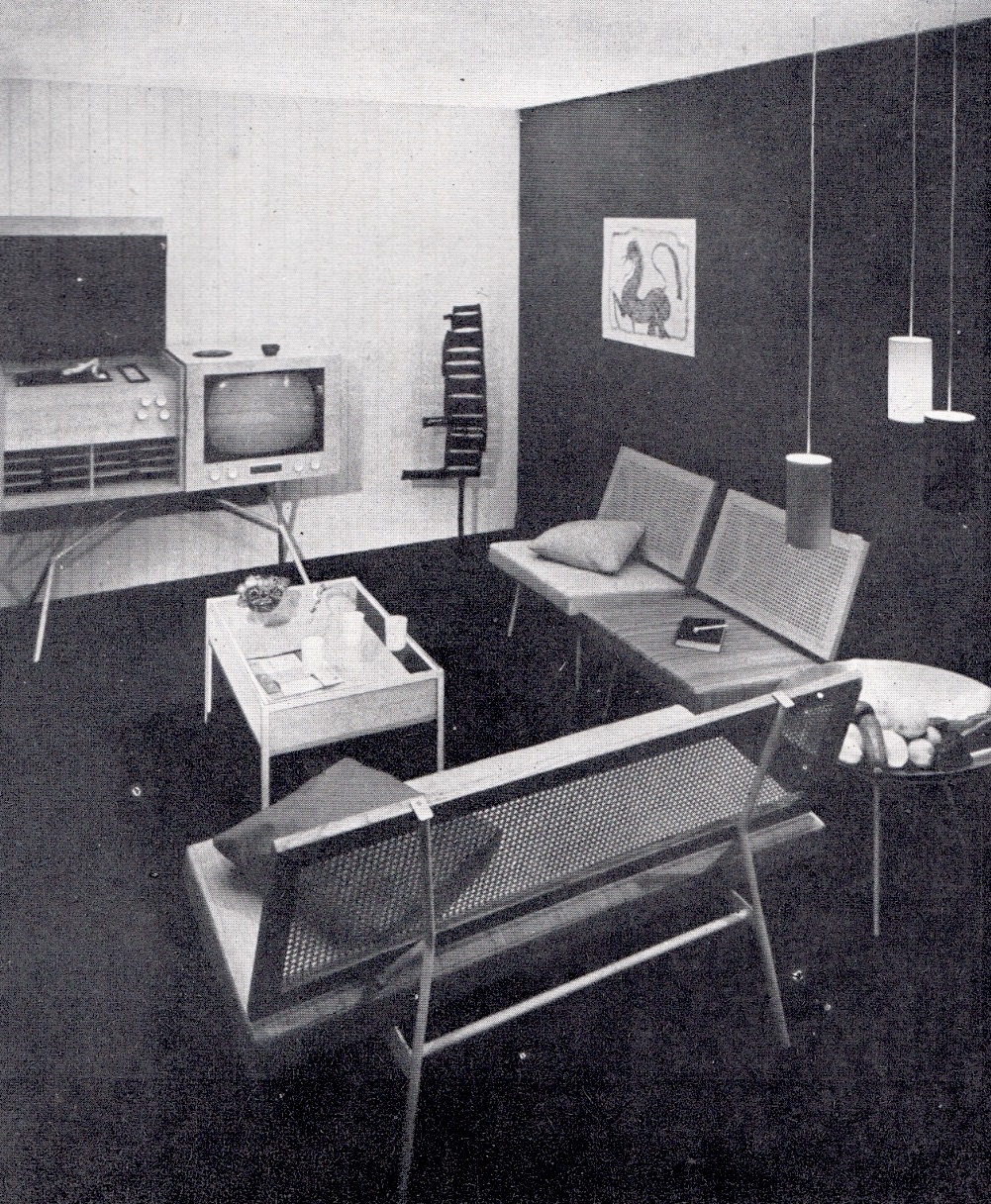

1955 Meubles TV

The designer, who had previously called on furniture-maker Robert Vecchione to produce his first stand at the 1953 foyer d’aujourd’hui, came to an agreement with this avant-garde producer to include several of his designs in his catalogue. He represented Meubles TV (Tricoire and Vecchione) at the Salon des arts ménagers, 1955 with a stunning collection featuring cylindrical white lacquer-coated metal legs and pioneering seats composed of a kind of nylon latticework20. With the television becoming a feature in more and more French homes, he joined forces with Pathé-Marconi and Meubles TV to create a prototype for a television that would have a record player and speakers, as well as a screen. At one end of the stand he showcased one of the most unusual of his designs: a fruit bowl in deep-drawn aluminium made by the light fittings manufacturer Pierre Disderot. This design was probably produced by TV as well, although the exact number produced seems to be a secret.

1957-58 The advent of stretch fabrics

Having just moved into the rue de Seine in 1956, (also the year in which his second child, Fabrice, was born), Pierre Paulin threw himself into a process of reflection driven by human ergonomics and his desire to create seats that were above all comfortable. In his first designs for Thonet, the load-bearing elements were not directly attached to the main body of the chair. Subsequently, he concentrated on another avenue of research, the use of synthetic foams with no visible load-bearing elements at all. In 1957, with Thonet’s help, he began to research the use of stretch fabrics of the type employed in the clothing market. After months of tests, Paulin and Thonet registered a patent, initially applicable to designs destined for mass production and later extended to works designed for exhibitions and interiors. Two years down the line, he was to break new ground for Thonet with an innovative range of seats boasting removable chair covers made from industrial stretch fabric (the model CM194 low chair design and the CM195 armchair). This meant it was now possible to remove the chair cover and wash it – a major selling point. The chair had become the main way in which he expressed his creativity,

undoubtedly influenced by his uncle, Georges Paulin, the car designer. ‘How do you make a chair in which you can sit in a way that’s comfortable? It’s a very tricky question. As soon as you start using new materials, everything changes. Above all, you need to like the human body, its contours and its morphology.’

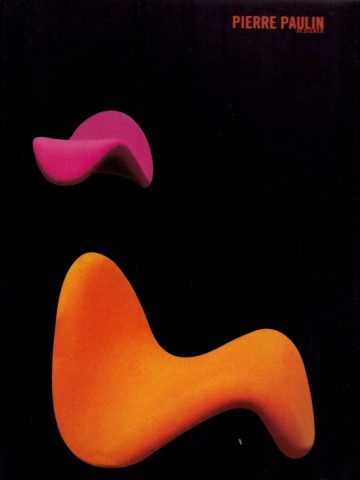

1958-1977 The Dutch adventure – Artifort

Paulin first met Kho Liang le and Harry Wagemans, respectively, aesthetic consultant/designer and CEO of Artifort at Expo ’, Brussels, where he was showcasing his work. Ready to try something new, he applied for the position of designer in the company. His innovations and experimentations at Thonet won over the management team of the Dutch firm, ahead of the likes of Pierre Guariche, Michel Mortier, Joseph-André Motte and Alain Richard. Thus began his long partnership with Artifort. The following year heralded a revolution in the firm’s output, with the development of a completely new chair, the model 560, known as the Mushroom. This design did away with legs, these being replaced by a simple wooden disc. The foam upholstered tubular metal frame was completely hidden by a removable cover, thanks to a combination of high-precision moulds and the material’s stretchability. The disappearance of obvious structural elements and their replacement by a basic shape which would evolve over time, as illustrated by the different models brought out by the firm, reached its height with the model 577 chair, the Langue. This cutting-edge experimentation at Artifort also gave rise to the model 675 chair, the Butterfly, in 1963, the model 545 armchair, the Tulip, in 1965, the high-back lounge chair model 784, the Concorde and finally, the model 582 chair, known as the Ribbon chair in 1966.

The 1960s, the journey from shaping materials to shaping space: Interior design

The designer took on the job of designing the exhibition stands of a number of the manufacturers for whom he was working – immediately demonstrating his feel for space at his first appearance at the Salon des arts ménagers in 1953 – and later on for Thonet and Meubles TV. !

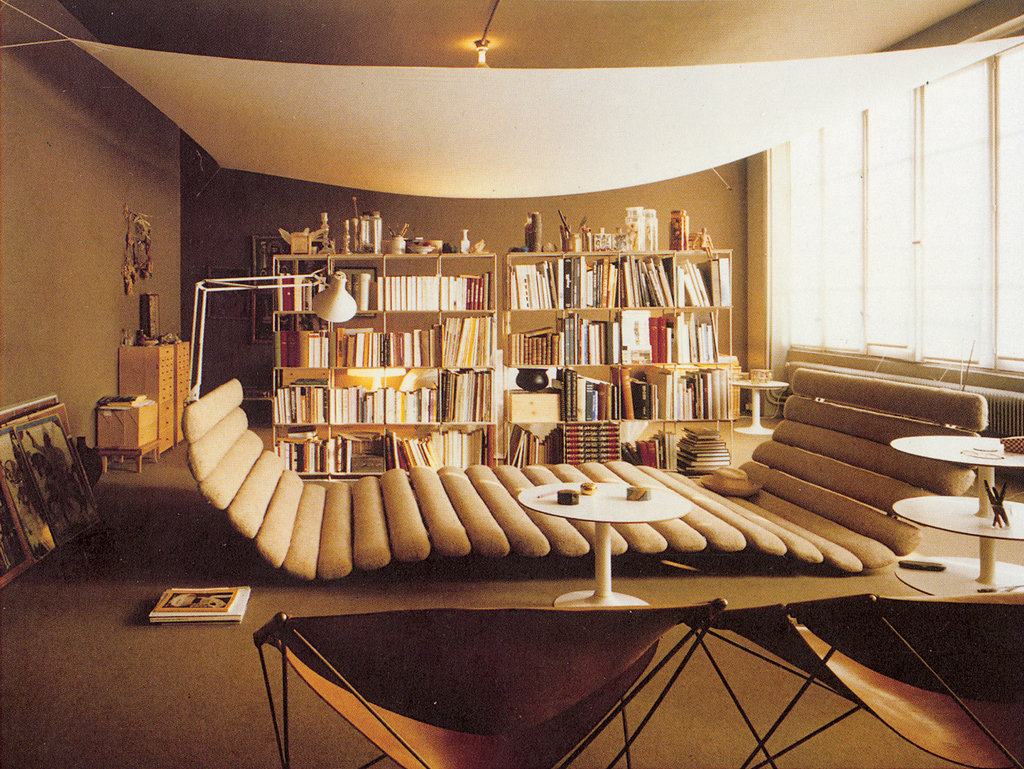

In 1960, the award of the Prix René Gabriel further burnished his reputation, enabling him to win several interior design contracts such as the interiors of the Green Room at the State Broadcasting House, the Maison de la Radio in 1961. He devoted more and more effort to studying interior design. Early works included the exhibition stands for Bertrand Faure, sole agent for Artifort, for the salon de l’automobile car show, the office of Dior’s artistic director, Marc Bohan and the front window of the Roche et Bobois showroom. He also worked on exhibition design for the Salons des arts ménagers of 1962 and 1966 before going global, in the shape of the interior design of the Dutch firm Artifort’s showrooms right across the world. These projects allowed him to experiment with what is now known as an ‘interior double skin’. The classic example of this technique was created ten years later in the French President’s private apartments in the Elysée Palace. His thoughts on the use of fabrics, weaving and the use of space were shaped by his travels in the Middle East, where he discovered rugs had a multi-purpose use in tents, being employed to cover the floor but also extending to partially cover the tent walls. This interest in how space is used in different societies took him all the way to Japan, which he visited with his wife in 1963. These experiences inspired him to create the Tapis siège rug-cum-seat and ‘Tatami’, Japanese-style décors which were exhibited to the public at the Salon des arts ménagers, 1965. Both these designs were rooted in the culture of hospitality that characterized the eastern way of life. As such, they represented a definitive break with one tradition to create a whole new world22. One project which never actually came to fruition (for the French Ambassador’s residence in Tunisia in 1972), gave him much food for thought in relation to lifestyle and modular design. He implemented some of these ideas in his creation of a series of models for H!erman Miller.!

1968 Mobilier National / ARC (Atelier de Recherche et de Création)

With Pierre Paulin already enjoying global renown, Mildred Constantine, a curator at MoMA, New York began to develop a keen interest in his work. As a result, the gallery acquired examples of Paulin’s earliest chair designs in 1968. At around the same time, the Chicago Athenaeum: Museum of A!rchitecture and Design awarded him its Design Award of Interior Designers.

It was also in 1968 that he began a fruitful partnership with the Mobilier National (a state body charged with supplying furniture to official state residences) and its head, Jean Coural. Pierre Paulin joined forces with Olivier Mourgue in the interior design of the maison de la Culture in Rennes23, then partnered André Monpoix and Joseph-André Motte in designing new interiors at the Louvre. This project had been initiated by the young administrator of the Mobilier National (formerly the garde meubles royal, the royal furniture repository) and Michel Laclotte, chief curator of painting and sculpture at the Louvre, with the support of Minister of Culture, André Malraux. The project lasted four years and included everything from selecting works of art for the areas in question, the interior design and the colour scheme. The three men also took charge of the lighting and the creation of display cases. They were also the first to put a protective barrier between visitors and the works on display, separating the works of art from the historical décor of the building. Furniture was also a part of the project, in the shape of the La Borne multi-seater low seat by Pierre Paulin. The Louvre, a place that celebrates the heritage of the past, became a place of inventiveness and creativity, eyes firmly fixed on the future.

This public sector contract for the greatest museum in the world with André Monpoix and Joseph- André Motte encompassed interior design work on the Grande Galerie, the Salon carré and the pavillon de Flore. The furniture was produced in close cooperation with the Mobilier National and l’ARC. He put this experience to good use three years later at Expo 70 in Osaka, where he exhibited the prototypes of the Amphys multi-seater sofa and the Elysée table, produced by l’ARC, for the first time.

T!he 1970s-80s: From shapes to systems!

Shortly afterwards, in 1971, his friendship with Claude Pompidou led to a contract from the French state – the redesign of the interiors of the private apartments of French President, Georges Pompidou. His experimental designs – the office of Dior’s artistic director, Marc Bohan and Bertrand Faure’s stand for the salon de l’automobile – along with the extensive research he’d carried out on the use of synthetic fabrics as a meta-structure – now came together perfectly in the Presidential apartments project. He designed the smoking room, the picture gallery, dining room and the dressing room of this magnificent mansion, creating a new, flexible, fabric wall that was separate from the walls of this listed building, and designing a range of cast aluminium furniture. He also installed indirect lighting, produced in double-quick time by Verre Lumière and created cushion style seats featuring a range of fabrics which could be taken off and replaced; ‘I was entrusted with the interior design of the rooms and was advised not to let anything touch the walls. So I created a new ‘lining’ for them, making rooms within rooms’.

Pierre Paulin met Maia Wodzislawska in 1969. Maia had founded the industrial design agency Architectural Design the year before and had been responsible for promoting and marketing the firm since the off. Being increasingly interested in industrial design, Pierre Paulin eventually joined the agency in 1975 and ADSA & Partners came into being. They worked out of premises on boulevard Raspail with their new partner, Marc Lebailly, a psychoanalyst and sociologist, for prestigious companies like Citroën, Matra Simca, Saviem, Thompson and Le Creuset…At this time, Paulin saw design as the creation of a system of signs, forming the core round which social structure was built. After divorcing his first wife, he married Maia Wodzislawska in 1982. They had a child together named Benjamin. At the beginning of the 1980s, the Elysée Palace and the Mobilier National enlisted his services again for the creation of a range of furniture for ministerial offices, which were experimenting with a return to the use of wooden furniture. In 1984 he worked on the office of the new Socialist President, François Mitterrand and for the city of Paris, including the Tapestries Room in Paris town hall.

His contribution to his field was recognized in 1987 with the Grand Prix National de la Création Industrielle. This marked a fitting end to his long partnership with the mobilier national, with his final project being the interior design of the hypostyle in the palais d’Iéna, the headquarters of the Conseil Economique et Social built by Auguste Perret in 1939.

The 1990s: from retirement to design legend

In 1993, Pierre Paulin left the ADSA & Partners agency and moved to the Cévennes with his wife. Here he embarked on a new kind of relationship with the natural world, which he had often used in the past as an inspiration and even a template for his work in both private homes and public buildings. The natural world offered him answers to questions about techniques and shapes, but it was also the source of an instinctive flair, which he used in the creation of movable internal fabric walls, other structures, even down to the ‘organic’ shape of his seats. ‘I was self-taught in terms of how I perceived the world of shapes and forms. It was pure instinct’ .!

The significance of his work as a designer gained gradual recognition, after manufacturers restarted production of a number of his designs, beginning with Artcurial at the end of the 1980s, followed by Tom Dixon for Habitat in 1999 with Amphys and Mushroom, not forgetting smaller production runs of the Dos à Dos chair and the Cathédrale table by Paris-based gallery and producer Perimeter.

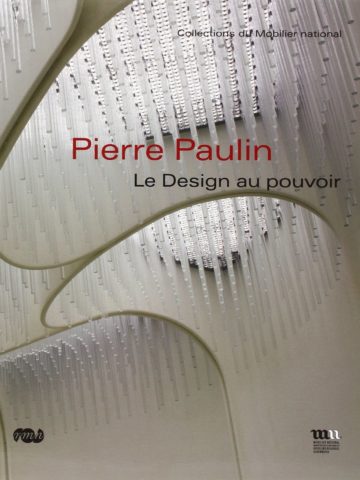

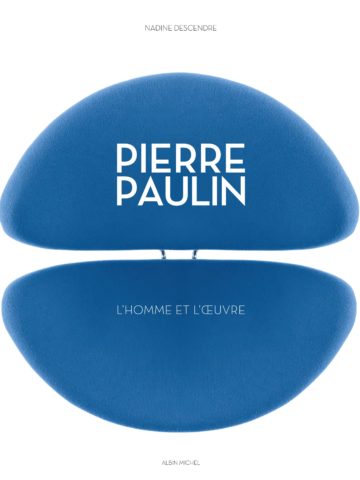

In 2007, with Paulin’s permission, Artifort finally re-issued several designs. Shortly after, the Villa Noailles art gallery in Hyères paid tribute to him with its exhibition, ‘Pierre Paulin, superdesigner’. In 2008, the Maison et Objet trade fair awarded him the title of designer of the year after his retrospective at the Mobilier National, ‘le design au pouvoir’ and the major exhibition devoted to his work by the musée du Grand Hornu, Belgium. He was pleased to accept these accolades, even so late in the day, given that he had always felt he had not been appreciated in his own country. Pierre Paulin died in June 2009, having received both critical and wider public acclaim for his work.

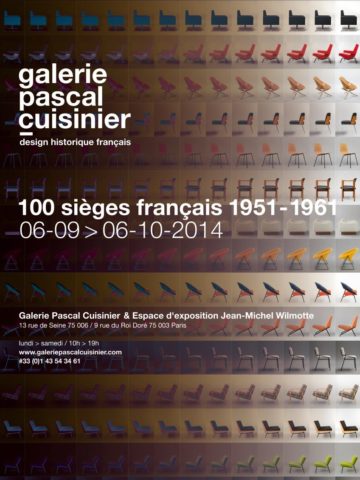

Since 2014, designer furniture maker Ligne Roset has been updating the first designs from the ‘ideal apartment’ of 1953, including some models produced by Meubles TV like the model 118 low sofa with wooden legs and the model 145 chair, as well as designs made by Thonet such as the CM141 writing desk and the model CM191 low table. !

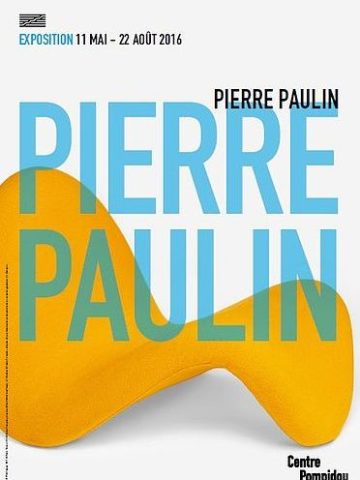

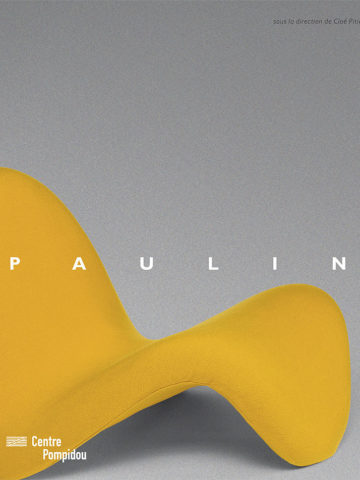

In 2015, the Musée National d’Art Moderne / Centre Pompidou put on the biggest retrospective ever of the designer’s work, spanning his entire career and featuring several designs from his very early period. Models from this time had rarely been put on public display, because they were produced in v!ery small numbers and are now virtually impossible to locate. !

After his death, many figures in the art and design world spoke of their admiration for him, especially Philippe Starck, who recognizes the timeless quality of his work, and Erwan Bouroullec who said: ‘he changed the way we look at just about everything: production processes, how furniture was used, the very concept of comfort, he blazed a trail for the rest of us’26. Fashion designer Azzedine Alaia collects his creations and also organized an exhibition at his showroom to mark Paulin’s 80th birthday.

Chronology

1947 / Studied at the École Camondo to 1950

1950 / First prototypes/armchair and cradle

1951 / Joined M.Gascoin agency with Guariche, Motte Mortier, Philippon, Lecoq, Richard

1952 / 1st interior design project/Maison Jalou/St Pry - Range of wooden furniture/Fernand Quin

1953 / La Maitrise/Galeries Lafayette – Paris

Discovers American design in Interiors

Begins partnership with Meubles TV Abraham, Guariche, Richard, Monpoix.

1st exhibiting at the Salon des arts ménagers

1954 / Partnership with Thonet until 1967

Exhibition/stand design for Thonet/Arts Ménagers

1957 / 11th Milan Triennial

1st Triennial of French Art, Paris

1958 / Meets Kho Liang Ie and Harry Wagemans from Artifort.

1959 / Gold Medal from the Société d'Encouragement à l’Art et à l'Industrie

1960 / 12th Milan Triennial

René Gabriel Price

1961 / Interior design of: Marc Bohan’s office at Dior

Front window of Roche et Bobois showroom

Maison de la Radio project

1963 / With Monpoix and Couturier, works on the general design of the Salon des artistes décorateurs exhibition until 1965

Mildred Constantine MoMA curator, develops an interest in Paulin’s art

1967 / Musée du Louvre with Motte and Monpoix

1968 / Design Award, Monza Italy

1969 / Design Award of Interior designers - Chicago

Works put on display by MoMA

1970 / Expo 70 - Osaka

Award at Eurodomus

1971 / Work on the Elysée for Président G. Pompidou

1972 / Herman Miller project

1975 / Founding of ADSA with Marc Lebailly

and Maïa Wodzislawska

1978 / Work on the official apartment of the Pompidou

museum’s Director

1983 / Resources Council Award (USA)

1984 / Work on the Elysée for President F. Mitterand

1985 / Salons des tapisseries/Paris town hall - Hypostyle in the Palais d’Iena

1987 / Grand Prix National de la création industrielle

1988 / Exhibition at école des Beaux Arts/Nîmes

2007 / Exhibition at Villa Noailles - Hyères

Exhibition at Azzedine Alaïa - Paris

Works put on permanent display by MoMA

2008 / Designer of the Year/salon Maison & Objets

Exhibition at Mobilier National - Paris

Exhibition at Grand Hornu - Belgique