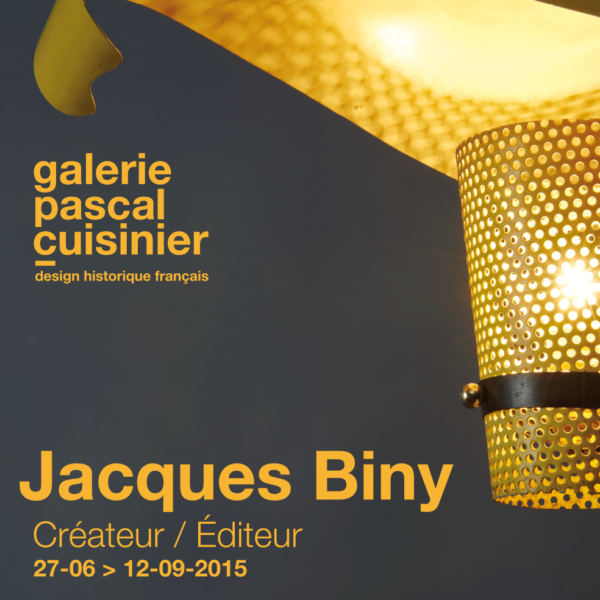

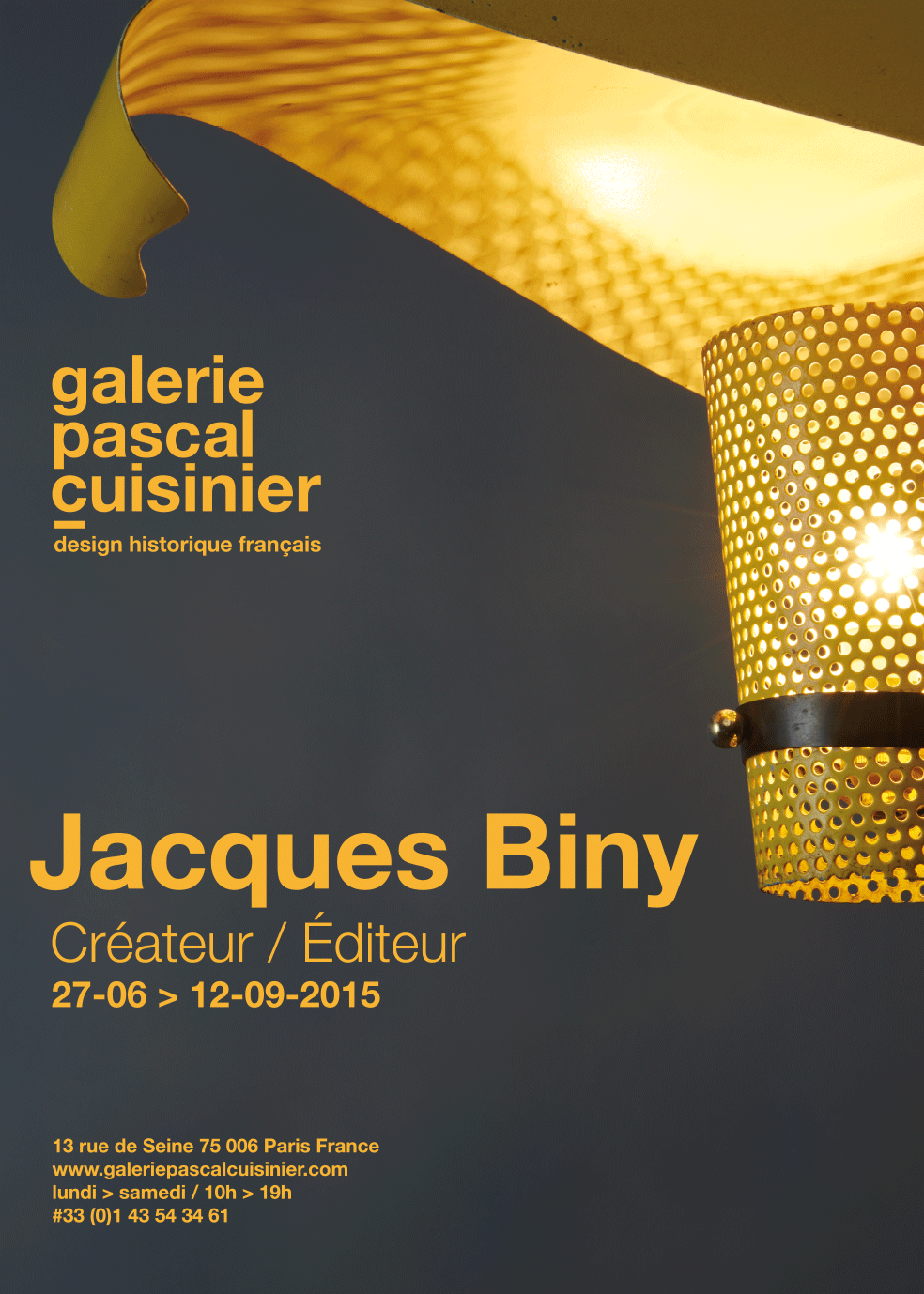

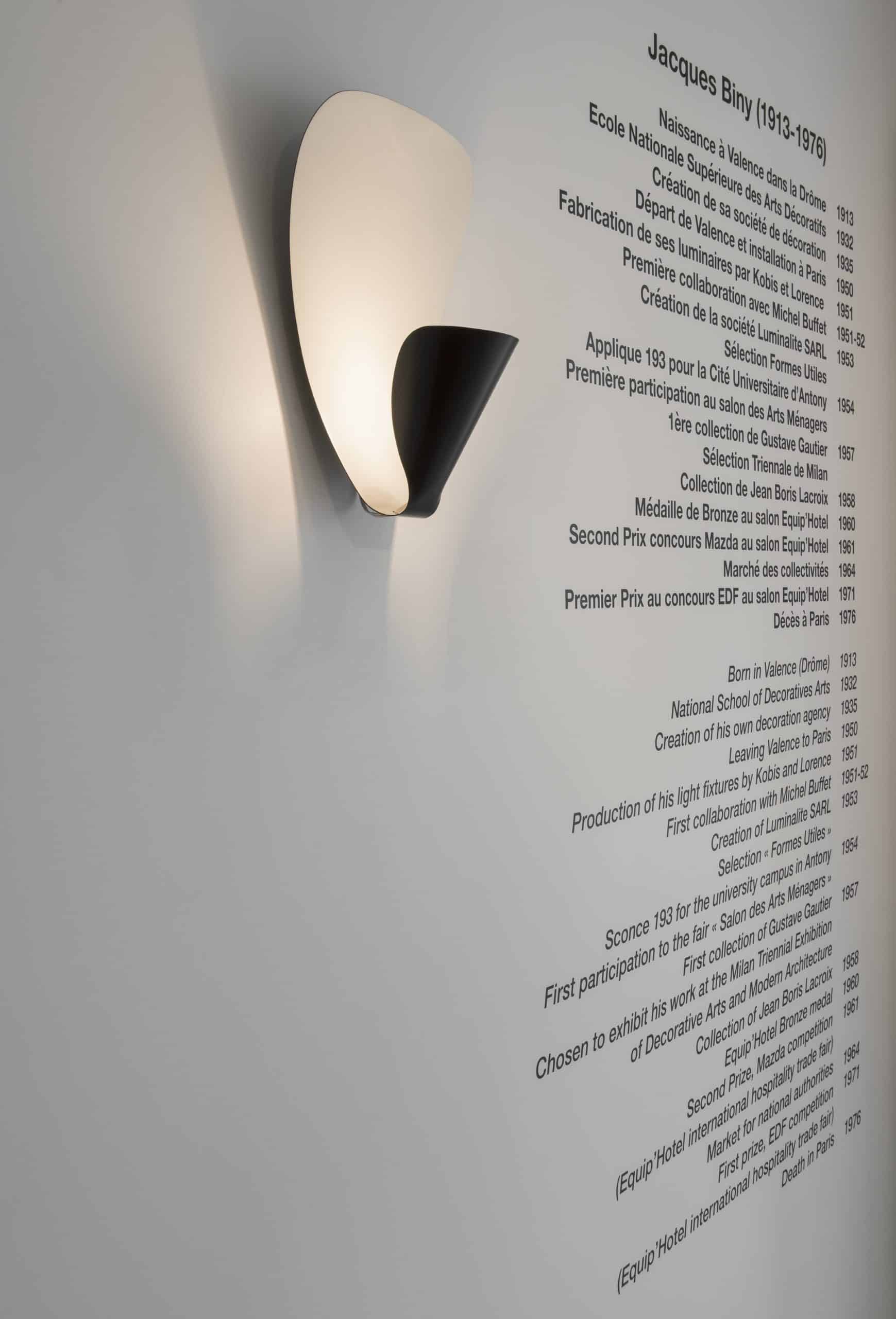

Jacques Biny, Designer/Producer

27/06/2015 - 12/09/2015

On the occasion of the International Year of Light launched by UNESCO and after a first show at Design Miami/Basel in june, the Galerie Pascal Cuisinier has dedicated this exhibition to a solo show of the work of Jacques Biny, presenting an exceptional collection of his lighting pieces, the fruit of eight years of research.

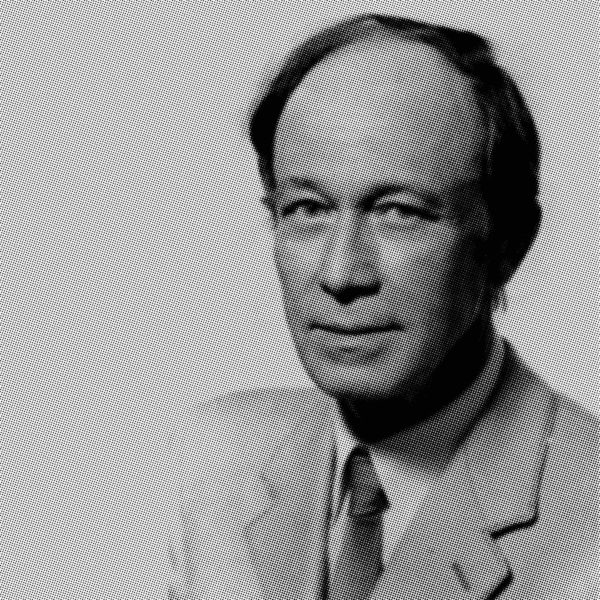

Jacques Biny was one of the most important French lighting designers from 1950 to 1970. Unlike most designers, he also manufactured designs and worked in partnership with some of the best designers of the time, including MichelBuffet, Jean Boris Lacroix and Gustave Gauthier. Together, they set out to forge a new future for this field.

A graduate of the École Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs de Paris, Jacques Biny settled in his home town of Valence inorder to practise his profession of interior designer. Confronted by a lack of light fittings on the sites he was working on,he decided to design his own, which he then offered to his clients. Following this experience, Jacques Biny returned toParis in 1950, founding his own contemporary light fittings production workshop, Luminalite, three years later.

Modern and pioneering, Jacques Biny produced a range of sophisticated light fittings for the home, using new materialssuch as perforated sheet metal and Perspex. With each stroke of his pencil, shapes morphed into radical new forms, mostly divested of their decorative function. In the 1960s, he was appointed lighting designer for large-scale projectssuch as major cinema, Le Palace and the Préfecture (administrative offices) of Valence and the shipyards of SaintNazaire.

For this year’s Design Miami/Basel, Pascal Cuisinier has decided to stage, in the most literal sense of the word, a show comprising of Jacques Biny’s finest creations. The stand has been designed in the same manner as a theatre, with black curtains in the wings and lighting inspired by director Robert Wilson’s work. A luminescent whitebackdrop à la James Turrell completes the display.

This exhibition, organized by Galerie Pascal Cuisinier, took place from 16 to 21 June 2015 in Basel, before moving to Galerie Pascal Cuisinier’s exhibition space in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, Paris, where it was shown from 27 June to 12 September 2015.

LIGHT FITTINGS AFTER THE SECOND WORLD WAR

French light fittings from the 1950s are without doubt amongst the most attractive, innovative and rarest designs of their kind to be found anywhere in the world. However, they are also amongst the least well-known.

The late 1940s was a time of remarkable scientific progress in terms of research intolighting. Journalists brought these developments to the attention of the wider public, demonstrating how they could be applied to the domestic environment. A whole generation of designers including Pierre Disderot, Pierre Guariche, Jacques Biny, Robert Mathieu and Jean Boris Lacroix took a close interest in these happenings. Some were graduates of the Ecole Bréguet technical university, which specialized in electrical engineering, and they were fascinated with how they could organize andarrange light fittings in the shape of designs destined for use in the home. Otherswent as far as to set up their own production workshops where they could bring theirown vision of modern light fittings to life.

At this time, the market was largely dominated by bronze light fittings or neo-fortiesstyle designs – all gilding and lampshades – not at all suited to the requirements of the modern age ushered in by the early 1950s. With memories of the war fading and a brighter future seemingly in store, comfort was what householders were looking for. Designers took this on board by creating their vision of what the modern apartment should be like – practical and sophisticated – as well as the furniture, chairs andlight fittings it would need. Each practical and technological advance representedsomething of a mini-revolution, generating, in turn, new shapes and forms.

To a specialization of the luminaire

Although almost every designer from this period addressed the issue of lighting at one stage or other in their career, some, such as Pierre Guariche, made it their speciality, even their passion. Immediately after graduating from the Ecole des Arts Décoratifs in 1949, he began setting out the principles of lighting design and use in the home – principles that are still followed today. He also invented many modernlighting fixtures. Galerie Pascal Cuisinier is a real ambassador for this lighting genius,having devoted a retrospective exhibition to his work in 2012, which featured almost all of his designs.

His encounter with Pierre Disderot, who was also a graduate of an electrical engineering school, provided him with an opportunity to create and experimentwith his designs. Pierre Disderot founded a light fittings manufacturing firm which produced many modern light fitting designs in France over a forty year period. His commitment to this field was such that he opened a workshop specifically fordesigners to develop their own models.

The Disderot workshop gave many designers the opportunity to work on theircreations. However, some figures on the light fittings scene chose to go it alone, like Robert Mathieu, whose work is to be exhibited in two years’ time at GaleriePascal Cuisinier, and above all, Jacques Biny.

Luminalite, birth of a brand and collaborations

Jacques Biny, who also graduated from the Ecole des Arts Décoratifs, found that thefew light fittings manufacturers in existence in 1950s France did not really believein him, either in relation to his interior designs or to the modern lighting designs he developed.

He began by subcontracting the production of his designs to Kobis et Lorence,but it quickly became apparent that this company’s approach to aesthetics and itsproduction tools would lessen his creative room for manoeuvre. It is very possible that this company, which was specialized in gilt bronze designs, found the productionof chrome items difficult. Likewise, Kobis & Lorence did not possess the necessarypress brakes to work with sheet metal, given that they were above all well-knownfor their castings. Biny decided to devote himself to light fittings, founding his owncompany Luminalite and setting up his own production workshops at rue de la Folie Régnault, Paris.

Jacques Biny recruited some of the best designers of the period. For instance, Jean Boris Lacroix, a star of the Modernist movement in the 1930s, produced a remarkable range of designs for Luminalite during the Fifties. Then there was Michel Buffet, a very young designer whose creations have something of an iconic status today,and are extremely difficult to find. A whole generation of interior designers like LouisBaillon and Gustave Gauthier were also involved. However, although Biny forged many partnerships, he nonetheless designed the majority of his creations himself.

Practicality and simplicity, the signature Biny

His approach to designing involved a great deal of research. He played around with all manner of variations on a theme – whether a shape or form or a wider lighting design principle. His goal was to create a bedside lamp that would project a light strong enough to allow someone to read in bed without blinding the person they were sharing the bed with. This led him to create dozens of elegant wall-mounted lights which directed some of their illumination where it could be used by a reader. The subsidiary portion of the light was directed up the wall towards the ceiling. He worked obsessively at trying to improve the quality of the light created, using diffusing strips, Perspex and lenses that concentrated the light in one place.

These designs are seen as an aesthetic success today. At the time, they were most remarked upon for their practicality and simplicity. There were no decorativeflourishes, rather carefully folded, lacquer-coated sheet metal which could be black,white or sometimes in other colours. The overall style was understated, elegantand certainly not flashy. The watch words were restrained and sophisticated, lightand practical. Biny created variants to cater to different niches in the home – wall-mounted lights, floor lamps, ceiling lights and table lamps.

Galerie Pascal Cuisinier has set out to tell the story of this great French designer through its exhibition of his work, just as it did with Guariche and just as it intends to do with Robert Mathieu

Although this exhibition focuses on the first phase of his artistic output, from the 1950s to the early 1960s, his career doesn’t end there. Biny’s expertise in designinglighting for homes led him to submit tenders for larger-scale local authority projects. As a result, in the course of the 60s and 70s he built up a range of highly-technical solutions, frequently for use in hospital environments. This was brought to an abrupt end by his untimely death in 1976.

The desire to respond to a function

Jacques Biny’s work is particularly noteworthy for its resolutely practical focus. Eachlight was designed with a particular location in the house in mind and the way inwhich the design projects its light was tailored to that specific location.

Light intensity and how the light is focused were driven by what would be the mostappropriate use of light in a given situation. Light could be reflected, indirect or designed to create an ambience (360° projection). The fittings designed by Biny aremade from sheet metal that is folded, curved, cut, welded, assembled together and then given a protective layer of lacquer.

Biny plays with angles and curves, blades, ribs, perforations, slits and veiling glare. Sometimes he added a brass tube, bronze fastenings, a mounting plate in contrasting materials, a glass sphere or a Perspex strip.

He put contrasts to good use: filled space and vacuums, black and white, light anddark, visible elements and hidden elements, core shadows and cast shadows… he was able to sculpt and shape light because he was completely at ease with his subject and medium.

Shapes are always simple, but not lacking in imagination. Finishing touches are never merely decorative. Although a thread may be seen running through his workand he frequently ‘signed’ his creations by means of a little conical bronze screw, his output cannot be categorized in terms of a clearly-defined style.

There is nothing superfluous in Jacques Biny’s designs – everything is there for a reason, a function, all has been carefully thought out for a specific purpose. Hisdriving force was to create designs that combined form and function. He createdmultiple variations on a theme to try to arrive at the best solution. The infinitesimallysubtle differences to be seen in some models exemplify this painstaking approach, dare we say obsession, passion even.